The molecular pathology lab at the Medical University of South Carolina has begun checking COVID-19 samples for variants, including new, highly transmissible strains. It’s using a process called next generation sequencing that decodes the genes in samples of the coronavirus collected from infected people. That lets researchers see how the virus is changing over time and prepare for the impact that could have on how easily it spreads, how sick it makes people and how well vaccines may work.

Dr. Frederick Nolte

“It's a big deal now that we keep an eye on what's happening to the virus,” said Frederick Nolte, Ph.D., vice chairman of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine and medical director for clinical laboratories and the molecular pathology lab. “We have the capacity for doing it. We have the instrumentation, we have the expertise, we have the people.”

They also have a sense of urgency. In a blog for the Association for Molecular Pathology, Nolte raised the alarm, noting that the U.S. isn’t testing enough coronavirus samples to give the country the ability to slow or stop the spread of mutations. He called for collaboration between public health and clinical labs and more resources to change that.

MUSC is in talks with the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control to see if they can work together and share some of the federal funding designated for COVID sequencing.

“Hopefully we don't make the same mistakes we made during the diagnostic testing debacle, where every lab was trying to do the best they could without any real centralized plan or cooperation between laboratories. The CDC and the federal government are trying to foster that collaboration so more genotyping can get done,” Nolte said. “This could possibly aid in contact tracing if the results are available in real time.”

MUSC is proceeding for now with the help of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Abbott Diagnostics. Abbott makes some of the equipment MUSC uses in COVID-19 testing.

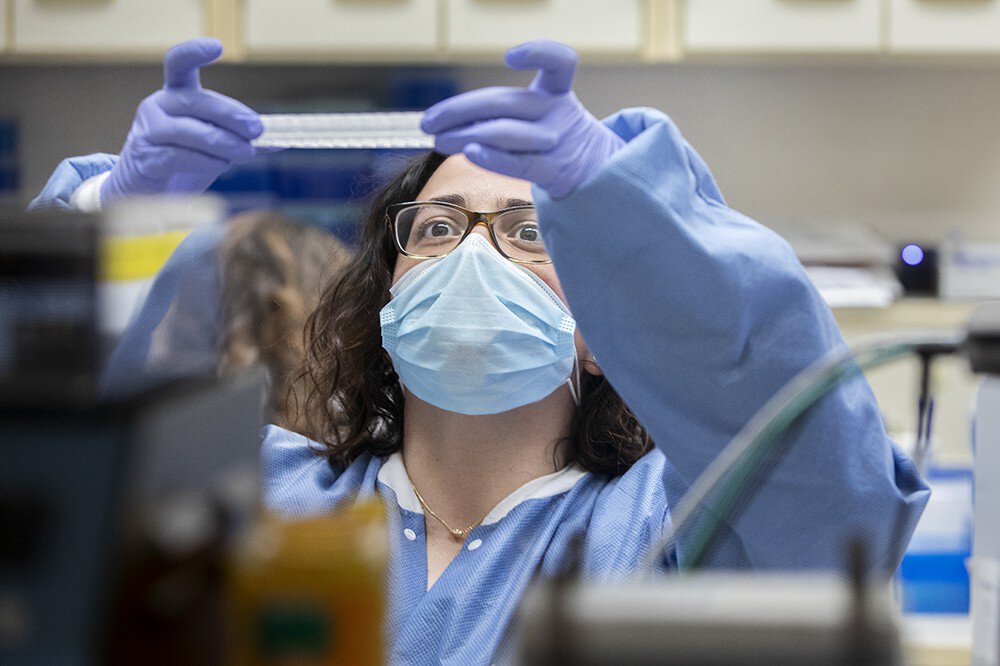

Julie Hirschhorn, Ph.D., serves as associate director of the molecular pathology laboratory and leads MUSC’s variant analysis efforts. “We’ve done two runs. We’re getting ready to do our third,” she said, referring to the practice of sequencing COVID-19 samples in batches.

A plate of indexes used to identify samples during the sequencing process. Photo by Sarah Pack

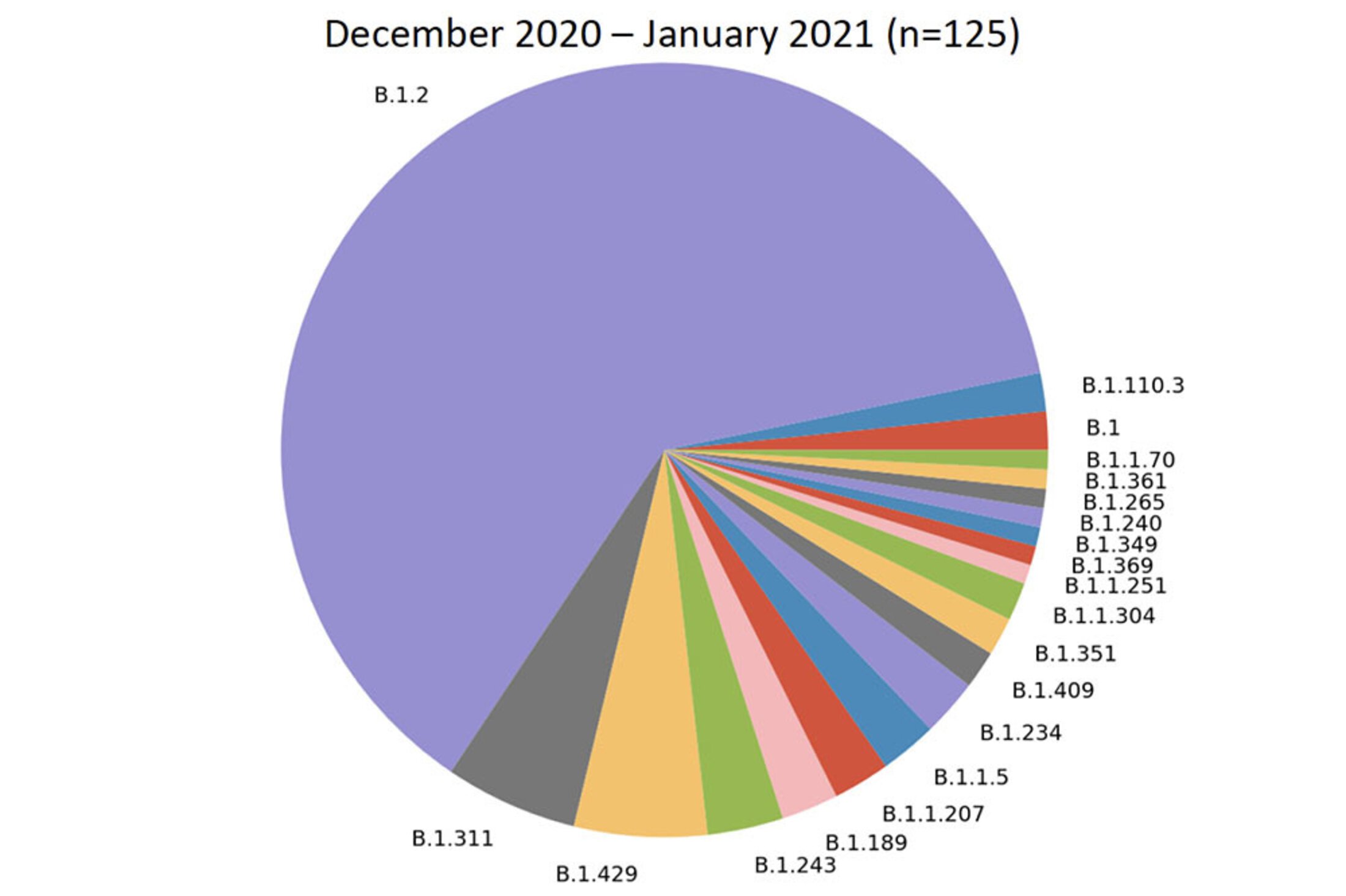

The two small runs they’ve done so far, with a total of 178 coronavirus samples, give a snapshot of how the virus has been evolving in South Carolina. In samples collected at the start of the pandemic, from March to June of 2020, the two major lineages were B.1, a largely European lineage that corresponds to the Italian outbreak, and B.1.110.3, a U.S. lineage linked to Florida. From July through November, the B.1.2 lineage, a U.S. strain, expanded to be the most prominent lineage. The B.1.2 lineage continued to expanded its reach between December of 2020 and January of 2021.

What does it all mean? Since the number of samples was so small, not a lot – yet. But there are a couple of takeaways from the sequencing so far. Bailey Glen, Ph.D., a specialist in pathology and laboratory medicine, pointed to one of them. “The biggest difference between what we’ve seen at MUSC and what we're seeing across the U.S. is the absence, at the moment, of the U.K. strain. I believe at the moment that's No. 2 in the U.S. and I didn't see it here.”

On the other hand, they did see some South African variants, including B.1.351, in the most recent samples at MUSC.

Maurer and Dr. Julie Hirschhorn prepare samples for sequencing. Photo by Sarah Pack

Both observations square with what SCDHEC has reported: only a handful of people are known to have had the U.K. variant in South Carolina. The number of people with the South African variant B.1.351 is higher.

Dr. Bailey Glen

But all of that is based on samples from the past. Hirschhorn said the next run, set for the next week or so, should give experts a better idea of what the state is dealing with now.

What’s happening elsewhere serves as a warning. In Brazil, a variant has been infecting people who had already bounced back from COVID-19.

Nolte said more sequencing is crucial, and his team at MUSC is ready to be a part of that. “Who knows what a lot of the minor variants are going to mean. If they become more widespread or they morph into something else all depends upon where those mutations are located, what kind of effect they might have on transmission, diagnosis, immunity - either natural or vaccine-induced immunity. Without a lot more surveillance, we're not going to have the full picture until it becomes a major problem.”

Recent Infectious Diseases stories