Celiac disease affects an estimated 1 in 100 people but most don’t get a proper diagnosis, according to the Celiac Disease Foundation. That’s a problem, because when people with the genetic condition eat food containing gluten, their immune systems respond in ways that can do serious damage.

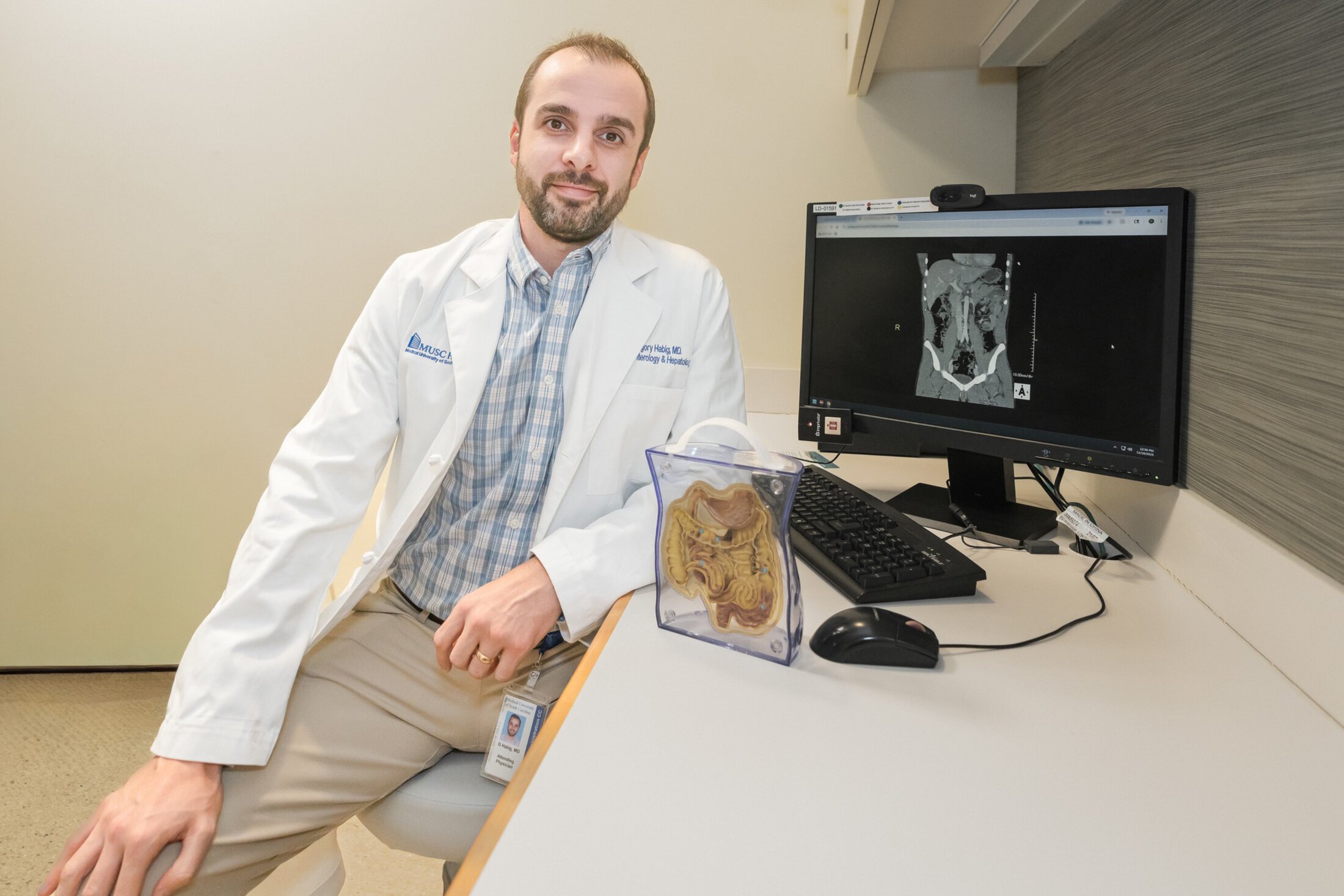

Gastroenterologist Gregory Habig, M.D., treats patients with celiac disease at the Digestive Disease Center at MUSC Health. In this Q&A, he discusses what the condition is, what it does to the body, the effects of going gluten-free and more.

Q: First, can you explain in more detail what celiac disease is?

A: It’s a medical condition caused by the body’s immune system reacting to a specific peptide within gluten, which is a protein in wheat-containing products. Rye, barley, oats, malt and brewer’s yeast also contain gluten.

In people with celiac disease, when they eat food with gluten, the body launches an autoimmune attack on the lining of the small intestine. It sees the gluten as what we call an antigen, or something that's a potential threat to the body, that triggers the immune system to respond.

This response results in serious damage to the lining of the small intestine, causing symptoms like diarrhea, abdominal bloating, weight loss and malabsorption of different nutrients. You can also have a lot of non-GI-specific symptoms.

Patients often develop things like iron deficiency anemia, fluid overload in their abdomen and elevations in liver function tests. Celiac disease can also cause issues like osteoporosis, certain dermatologic conditions and can even impact reproductive health. It's a systemic disease.

Q: How is it diagnosed?

A: The gold standard for the initial diagnosis of celiac disease is antibody testing. We look for certain antibodies that are elevated in patients with celiac disease when they are exposed to gluten. They can come packaged together in something we call a celiac panel, which looks at multiple antibodies that help us screen for celiac disease.

The patient has to be actively eating gluten before testing for those antibodies to be positive. If they're already self-diagnosed with celiac and they're confident that they have it, but they’re already on a gluten-free diet, they won’t have the antibodies.

After the antibody test, we do a confirmatory test with an upper endoscopy. During this endoscopy, we take biopsies of the lining of the small intestine to look for damage and confirm the diagnosis of celiac disease.

Q: When are people usually diagnosed?

A: It used to be thought of as a disease of childhood. But as we're getting better at diagnosing it and recognizing it. We're seeing a more bimodal distribution, both in younger people and then people in around their 60s, early 70s. It can, however, be diagnosed at any age.

Some people go undiagnosed for long periods of time because not everyone has very dramatic diarrheal symptoms or a lot of abdominal bloating that would cause them to see gastroenterologists. Sometimes, the symptoms can be very subtle, like anemia or a skin rash.

Q: Is there a downside, other than discomfort, to going undiagnosed?

A: Yes. People who have celiac disease and continue to eat gluten-containing products are at an increased risk for small bowel lymphoma. They're also at increased risk for some more benign, but still serious conditions, like iron deficiency anemia, osteoporosis and different nutrient deficiencies resulting from malabsorption.

Q: Can you talk more about that?

A: In your small intestine, you have these finger-like projections called villi. They help us absorb fluid and nutrients from the lining of the GI tract into our bloodstream to give our body the nutrition that it needs.

In people who have celiac disease, the villi become blunted or destroyed. So rather than having all these fingers to absorb nutrients, it's like a flat surface. You can't really absorb the things that your body needs when this happens.

Q: Can that be changed with treatment?

A: Yes. So if you go onto treatment for celiac disease, which is a strict gluten-free diet, the body heals itself. So over time, you'll have regeneration or reformation of those villi.

People can have dramatic and drastic recovery, weight regain and get back to good nutritional status with just adherence to a gluten-free diet.

Q: Does gluten sensitivity always mean a person has celiac disease?

A: No. There's something called a non-celiac gluten sensitivity, where people will have celiac-like symptoms of abdominal bloating and changes to their stools in response to eating gluten-containing foods. But they don't have that autoimmune damage going on.

So they may have a sensitivity to those foods, and they have symptoms in response to those foods, but they don't necessarily have the higher risk for things linked to celiac disease, like small bowel lymphoma or the other conditions we discussed that would need frequent monitoring with a gastroenterologist.

But anyone who thinks they have celiac disease should talk to their primary care doctor, who can assess the symptoms to look for other potential causes. They’ll usually order the celiac panel to look for the antibodies related to the disease or refer you to a gastroenterologist.

Q: If the answer is yes, somebody has celiac disease, what’s next?

Ideally, they get referred to a gastroenterologist who can look at the clinical presentation and not only assess the severity of symptoms but also help in monitoring for possible consequences of celiac disease and the challenges of adhering to a gluten-free diet.

Sometimes, people with celiac disease who are avoiding gluten still have symptoms like diarrhea and bloating. That can be from inadvertent exposure to gluten, so we screen their antibodies intermittently. Adherence to a gluten-free diet in those with celiac is a complete lifestyle change. They may end up having to get their own silverware, their own toasters so they aren’t accidentally exposed to others’ breadcrumbs.

It’s also important to keep in mind that ongoing symptoms, despite a strict gluten-free diet, including diarrhea and weight loss, can be coming from different but related conditions. They may go undiagnosed if you're at a center that doesn't have the knowledge and the history of treating celiac disease that a center like MUSC has.

Q: What about gluten-free foods – are they a good idea for everybody, including people who don’t have celiac disease?

A: Being on a gluten-free diet isn't necessarily the healthiest diet. Gluten-free foods need to get their flavor from something, so they often end up being very high-fat, sometimes very high-sugar or salt. They often are lower in fiber and have different micronutrients as well. When you look at nutrition science, it's not as healthy a diet as compared to a normal gluten-containing diet for people who do not have celiac disease.

I think people often look at products that say they're gluten-free and think that’s the healthier option, but I think part of that is just good marketing from the gluten-free companies.

Recent Digestive Care stories